Panfish are the largest, most popular, and widespread freshwater fish species in the nation. Because these species can be terribly prolific in certain waters, stocking is generally not required for other than species introductions or in highly used public fishing waters. But when the largest fish of any system get fished out, stocking won’t solve the problem. It degrades the fishery. Of increasing concern to fisheries managers and anglers, the absence of large panfish is hurting many fisheries throughout the country. The cause of this stunting is greatly attributed to overfishing and overharvest, leaving behind many small fish to further proliferate in the absence of the larger, breeding sunfish; thus creating an imbalanced fishery.

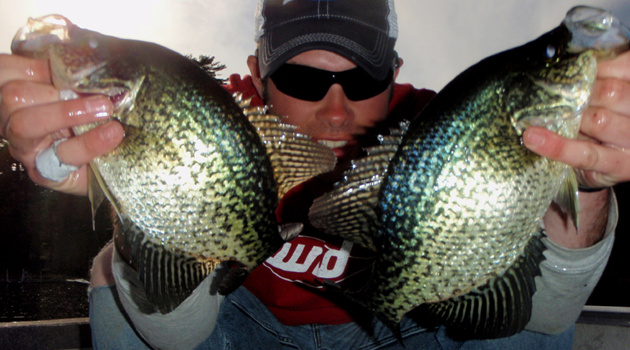

Panfish lovers are mourning over their loss of many former productive fisheries where saucer-shaped trophy bluegill and crappie once swam in abundance. Strong adult bluegill and crappie populations come and go. But when they go, they seldom return to their former selves, regardless of the conservation-minded measures and regulations that have been put in place to aid their resurrection.

The reasoning for this is attributed to the gene pool. When the alpha fish are removed, the future genetics are impacted.

With a decent gene pool to draw from, most freshwater fish species will grow well with good water quality and an abundance of food available to them. These watershed characteristics are important to bluegill and crappie for achieving maximum growth potential.

During the midst of our peak panfish season (May through July), I had the pleasure of exchanging thoughts and ideas with my friend and panfish expert, Jim Gronaw, who believes that quality panfish need to be treated with care.

During the midst of our peak panfish season (May through July), I had the pleasure of exchanging thoughts and ideas with my friend and panfish expert, Jim Gronaw, who believes that quality panfish need to be treated with care.

According to Gronaw, “Not all lakes are capable of producing or sustaining quality panfish species, regardless of angler pressure or harvest. But at least in my neck of the world, many anglers continue to harvest only, and I mean ONLY, the top-end crappies in any given system and complain when they have to settle for smaller fish.”

Managing panfish remains one of the most difficult problems facing biologists today. On a positive note, angler harvest rarely threatens the existence of panfish populations as sufficient numbers of fish remain to produce new generations of young fish. However, today’s panfish anglers are largely harvest-oriented and size-selective, usually removing the largest from the population rather than smallest.

Gronaw believes that given the cyclical nature of crappie spawns and growth dynamics, and the ancient concepts that we can ‘never’ fish down and deplete a fishery, it’s a wonder there are any good crappie waters around. “You can fish down size, but almost never fish down numbers in a panfish population,” he says.

Today’s anglers believe that size limits and stricter regulations have worked, despite that some improvements can be attributed to natural fluctuations in strength of year classes. In some instances, minimum-length limits have done their job, but anglers are unhappy over the fact they cannot keep as many fish as they were once able to.

“In my 61 years of fishing, I have seen many prime fisheries gutted due to the glut and overharvest of ONLY the larger bluegills, crappies or perch in a given system. Most of these have yet to return to their ‘glory years’ of producing 14 inch crappies or 10 inch bluegills. Releasing big panfish just makes sense,” says Gronaw, regardless of inevitable stocking or not.

With panfish, the term selective harvest must apply, as it does for Gronaw: “I keep mid-size fish for a meal. And it is no crime to keep an occasional hard-earned trophy. But I am thoroughly convinced that if more anglers would release large panfish, our waters would benefit greatly. It works for bass, trout, muskies, walleyes, and all other gamefish species….. and it works for panfish as well!”

Unsurprisingly, the likely largest hurdle to improved panfish quality is the attitudes of modern and technologically-advanced anglers. We are often at fault for exploiting new angling opportunities, and our actions can rapidly reduce a fishery to nothing before moving onto the next hot spot. If, and when it happens, there is nobody to blame for our depleted fisheries but ourselves.

More stringent regulations of angler harvest won’t improve panfish populations in all situations. For instance, look no further than the urban waters surrounding the Chicago metropolitan area. Some of these ponds and public lakes once held strong populations before they were exploited on the internet and then fished out by the masses. Could the fisheries have been protected?

Harvest regulations can work if they are applied to fisheries where fish longevity and growth are sufficient to provide increases in numbers of large fish. Identifying these situations has become an increasingly important component of modern panfish management.

Gronaw concludes, “Releasing of big panfish is the final frontier in catch and release fishing. It is sad that most of today’s panfish anglers, far more skilled than their those of even 10 years ago, refuse to believe that they have any part or responsibility in creating and maintaining good fisheries through good catch and release ethics.”

Moral of the story is….. Keep what you want, but don’t complain when all the fish you catch are dinks. Quality panfish lakes with populations of desirable sizes need to be treated with care.